On any given Saturday night in Southeast Texas, the sound of fiddles, accordions, and steel guitars can still spill out of community dancehalls and bars, calling people to the floor for a Cajun dance. If you stay long enough, chances are you’ll hear “Jolie Blonde.” Known as the Cajun national anthem, this waltz became a cultural landmark when Harry Choates recorded it in 1946. That single recording not only transformed Choates into a household name across the region but also played a pivotal role in pushing Cajun music beyond its local roots and into the broader American popular music landscape.

The Choates came from a family of Cajuns who, like many others, left Louisiana for Texas during the oil boom in search of steady work. They settled in the industrial hub of the Beaumont–Port Arthur–Orange area, better known as the Golden Triangle. Oil refineries, shipyards, and related industries promised jobs and higher wages; and with the influx of workers came their traditions—music, food, language, and the weekend dance. Cajun music in Texas can be traced back at least to the 1930s, when these transplanted communities gathered after long workweeks to relax, socialize, and celebrate with a fais do-do—lively dance parties that often stretched late into the night.

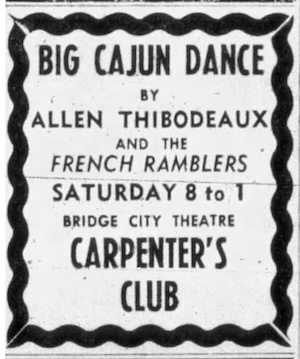

As Cajun music flourished in the Golden Triangle, certain venues became cultural landmarks. Places like the Club 88 and B.O. Sparkle in Bridge City—later renamed Sparkle Paradise—The Mecca in Nederland and Rodiar’s Club in Port Arthur were central to the scene, hosting live music every weekend for decades. Inside, the atmosphere was always electric: couples waltzed across the floor, children often slept on benches or in cars outside, and musicians kept the rhythm steady until the early hours of the morning. Bands such as Joe Bonsall & The Orange Playboys and Allen Thibodeaux & The French Ramblers became mainstays, running the circuit of venues that catered to the Cajun communities of Southeast Texas. Every Sunday morning the party continued over the airwaves with area disc jockey Tee Bruce and his Cajun Jamboree show.

While traditional Cajun music in Louisiana leaned heavily on the fiddle and accordion, Texas Cajun bands introduced subtle shifts in style. Influenced by the sounds of Western swing and honky-tonk that permeated Texas dancehalls, their arrangements often featured the steel guitar alongside traditional instruments. This gave Texas Cajun music a distinctive sound—still unmistakably Cajun, but with a more swinging two-step flavor that set it apart.

The Golden Triangle also drew talent from across the Sabine River. Zydeco great Clifton Chenier, widely hailed as the King of Zydeco, was a frequent draw, bringing a Creole flair that electrified audiences. Swamp pop groups like The Boogie Kings—often described as playing “blue-eyed soul”—also packed dancehalls, blending rhythm and blues with Louisiana soul and pulling diverse crowds ready to dance shoulder to shoulder. These crosscurrents made Southeast Texas a true melting pot of Gulf Coast music, where Cajun, Creole, country, and rhythm and blues all shared the same stages.

Although many of the once-iconic clubs have since shuttered, their legacies remain woven into the cultural fabric of the region. Today, Cajun music and dance are kept alive in Southeast Texas through community halls, church gatherings, and annual festivals that celebrate Cajun heritage. Families still gather on weekends for dances, young musicians learn the old songs, and crowds—old-timers and newcomers alike—fill the dance floor when the accordion starts to play. The venues may have changed, but the spirit of the music endures, as vibrant as it was decades ago.

Listen to the entire playlist here: