The Front Porch

The porch of a typical sharecropper cabin provided a place for relaxation, a place for laborers to find solace after long days in the fields. In modern day terms, the porch could be seen as an extension of a living room of cabins, as interior rooms often needed to be utilized for many household duties. The porch was also a place for social gatherings, offering a respite from the realities of daily life.

The porch also functioned as storage for various items of a home. A precursor to modern refrigerators, the icebox utilized a large block of ice that would slowly melt, cooling the interior of the box to preserve food items. Because of the mechanics of iceboxes and needing large ice blocks to be installed regularly to the machine, when they weren’t placed in kitchens, they would reside on the porch. There would often also be a pail of water on the porch to provide a quick way for laborers to clean themselves throughout the workday. Additionally, outside of the cabin laborers would often keep gardens and farm animals to produce food. Some sharecroppers and tenant farmers supplemented their diets by fishing and hunting animals such as rabbits and turkeys, but land use restrictions often prevented this. Many families raised chickens, geese and cows for personal means. These animals were a significant investment and provided essential dietary staples, so farmers had a high interest in protecting them. Foothold traps are often used to catch predatory animals such as coyotes and raccoons, rather than game animals such as rabbits or fowl, and would have provided ample protection for these animals.

Main Room

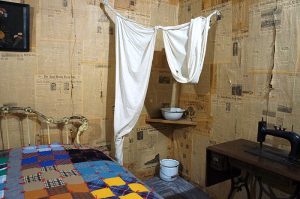

The main room of a sharecropper cabin functioned as the central point for most activities of a family. As homes of sharecroppers were often limited in space, rooms had to fulfill multiple purposes. Beds were often shared by the entire family to account for lack of space, and housework was made more arduous from the lack of electricity, plumbing and funds to cover household products. Providing a place for sleep, washing, and general utility for a full family, the main room of the cabin gives an insight into how laborers and their families fulfilled domestic duties.The nature of sharecropping changed how division of labor worked in formerly enslaved families. For many African American families, this meant the ability to divide women’s time spent working in the fields and working in the home. With less time spent laboring outside, women in sharecropping families had more time to complete domestic duties and household chores were often the sole responsibility of the women in the household.

Though they had more time to complete crafts, such as quilts or needlework, they were often limited severely by funds. Quilting has a long history as a creative practice both individually and collectively, but it was often a task of necessity for poorer women as balancing field work with domestic duties left little time for hobbies. The easiest fabric to obtain would be scraps, from old clothing and feed sacks, which would be stitched together with a middle layer of cotton for insulation. Occasionally women would collaborate on a quilt, but it was not the same social event as it was for those who were more well-to-do.Though relatively expensive, sewing machines provided a better deal for many sharecropping families than buying ready-made linens and were often a sound investment for many families. Sharecropping families had to account for a transient lifestyle as well as a limited budget, which meant that many large home appliances were impractical.

For families who could afford it, however, a sewing machine was a worthy investment. By the 1900s, several different companies produced mechanical sewing machines for domestic purposes. For sharecroppers and tenant farmers, owning a sewing machine to produce the family’s clothes and linens was far less expensive than buying ready-made clothing (especially for families with children). One didn’t even need to buy fabric: many women re-purposed the cloth from feed and flour sacks, a practice so common that companies began printing designs on the fabric. If a family didn’t have their own machine, they would often be able to use one owned by a nearby relative or neighbor. Even without any access to a machine, the expense of new clothing was so great that women sewed garments by hand.

Kitchen

The kitchen in a sharecropper’s cabin was a place to make and eat meals. In this cabin’s kitchen, there is a place to store foodstuffs, a counter to prepare food on, a wood-fueled stove, a small two-person table, and two chairs.

Due to a lack of plumbing and electricity, in order to keep things cold or wash vegetables/dishes, they had to be done outside of the kitchen. For example, people would store their food in an icebox, which is located on the front porch, for easier access because it required a large ice block to keep things cool.

Sharecroppers make their living by using the land surrounding them to grow and cultivate food. People would grow things to sell, barter and eat. Many had small personal gardens to grow fruits and vegetables such as sweet potatoes, peas, okra, watermelon, peaches, corn, lettuce, mustard, turnips, radishes, and collard greens. Whatever was not grown and cultivated on-site, such as flour, rice, sugar, coffee—had to be purchased. Families often bought these staples in large quantities at the beginning of the year, occasionally on credit from the landowner, rather than take frequent trips into town to shop. Alternatively, you could get dry goods from a traveling peddler, bartering eggs, or extra produce from the garden.

Families kept chickens and cows for their eggs and milk, but hogs were raised for meat. When it was time to slaughter the hog, it was a communal event. Men would catch, kill, clean and butcher the hog. In some communities, women and children prepared the meat into sausages or salted it for preservation and rendered the lard for cooking and other household uses. However, in some areas, men also took part in these tasks. Eugene Bullard recalled celebrating Juneteenth by slaughtering one to three hogs, distributing the meat throughout the community.

Outside

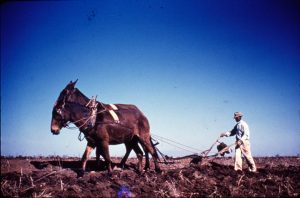

Sharecropping’s decline began in the 1930s, due to factors such as soil exhaustion, New Deal-era subsidies, and advancing agricultural technology. In a decade, the number of Texans living and working as tenant farmers or sharecroppers plunged: from 301,660 tenants and 105,122 sharecroppers in 1930 to 204,462 tenants and 39,821 sharecroppers in 1940.

Cotton cultivation continued in the Blackland Prairies where, as late as 1960, headlines in the Bryan Daily Eagle reaffirmed that “cotton [is] still king in the fertile Brazos Valley.” Since the mid-1800s, the Brazos Valley, or Brazos Bottoms, had produced lumber, livestock and corn as well as cotton. Thanks to its position on the railroads, the town of Navasota was an important center for processing and shipping. In this small town—the population peaked in 1940 at just over 6000—the Moore name loomed large.

The Moore family traced their origins in the Brazos Bottoms back to the Texas Revolution. In the early 20th century, brothers Harry and Tom were notable figures in the region’s economy and culture. Harry owned 8500 acres in nearby Allen Farm, producing cotton and cattle, and Tom grew cotton and corn on 2000 acres in Navasota. In 1956, the Bryan Daily Eagle reported that 65 African American families lived and worked on the Moores’ land. Harry Moore also participated in the Bracero Program, where the U.S. government arranged for Mexican laborers to support Southern and Southwestern agriculture. Originally introduced to compensate for the labor force lost to World War II, braceros worked in the United States until 1964, when growing dissatisfaction with exploitation at the hands of landowners and the sometimes violent racism from surrounding communities spurred the program’s end.

Thanks to photographs, some provided by Tom Moore himself, and personal records of their Brazos neighbors, we know the farm hosted a general store, where the tenant laborers and resident sharecroppers purchased their essentials and equipment. Stores such as these were an emblem of the sharecropping system: the landowner held control over the economy, constructing a system where the worker began the season in debt, and where their ability to repay depended on the whims of the climate and the market.

By 1970, Moore grew more corn than cotton (thanks to a contract with Frito-Lay). Mechanization and commercial demand meant that a corps of tenant farmers and sharecroppers was no longer needed. Their empty cabins remained on the land: then, in 1979, one was transported from Navasota to San Antonio to anchor an exhibition at the Institute of Texan Cultures.